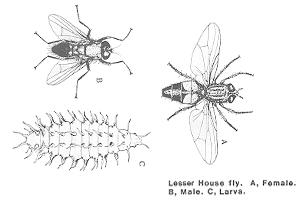

The lesser house fly or little house fly, Fannia canicularis, is somewhat smaller (3.5–6 mm (0.14–0.24 in)) than the common housefly. It is best known for its habit of entering buildings and circling near the center of rooms. It is slender, and the median vein in the wing is straight. Larvae feed on all manner of decaying organic matter.

They have a life expectancy of two to three weeks. They are often found on excrement and on vertebrate animals. Because of their oscillating between excrement and human food, they are considered possible disease carriers. The lesser housefly comes frequently into buildings and is noticeable by its peculiar, silent flight in the room center, where it circles down-hanging articles, particularly lamps. It changes the flight direction jerkily. This is a patrol flight, in which the males supervise, if necessary, their district and attack intruders. During short breaks and in the night hours, the flies sit on lamps or on walls and leave their small excrement marks.

Development:

The females lay their eggs in batches of up to 50 and may lay up to 2,000 eggs altogether. The eggs, which are white with a pair of dorsal longitudinal flanges or wings, can float in liquid and semiliquid decaying organic matter, especially poultry, cow and dog feces, kitchen waste such as the end of putrid potatoes or carrots, silage and compost, cheese, bacon, and drying fish. They are commonly found in garbage depots, wheelie bins, garbage trucks, and other places where food waste is stored. The eggs hatch after only two days (24 to 48 hours at 24–27 °C or 75–81 °F) and the larvae require six or more days to reach pupation, which lasts seven or more days, so they usually take about 2–4 week to develop into adults, depending upon temperature. The cycle repeats in very damp, putrid excrement, liquid manure, etc.

|

|

|

Control:

Producers must monitor fly populations on a regular basis to evaluate their fly management program and to decide when insecticide applications are required. Accurate insecticide and application rate records must be kept. Insecticides can play an important role in integrated fly management programs; however, improper timing and indiscriminate insecticide use, combined with poor manure management, poor moisture control, and poor sanitation practices, will increase fly populations and the need for additional insecticide applications. Although most fly insecticides are toxic to predators and parasitoids and can result in their destruction if used indiscriminately, selective application of insecticides can avoid killing these beneficials.